By: Bob Robb

Decades ago, before the compound bowhunting explosion, one of the great debates in the hunting community focused on rifle cartridges for big game hunting. The two key personalities in the debate were Jack O’Connor and Elmer Keith. O’Conner was a big believer in small, fast cartridges, while Keith believed in slower, larger-diameter bullets. Later came Roy Weatherby and his Weatherby magnum rounds, which took the smaller, faster bullet theory to another level.

There was no clear-cut winner in this debate. After all, if you place a bullet in the vitals of a big game animal it will get the job done regardless. But it’s one that I think of often when the topic of arrow weight for bowhunting comes up. Because even the fastest arrows have a horribly arcing trajectory, at first blush most archers believe they need to do whatever needs doing so they can shoot a lightning-fast arrow. To do this they think they need to shoot the lightest arrow they can pump through a bow that’s been cranked up to maximum poundage.

If you’re one of them, to you I respectfully say, “Bunk.” After decades of bowhunting everything in North America, from gophers to grizzly bears — and whitetails as small as the diminutive Coues’ and Carmen Mountain subspecies up to the big-bodied bucks that inhabit western Canada — I have come to believe in the words of Roman dramatist Publius Terentius Afer (190-159 B.C.), “Moderation in all things.” It’s all about being able to hit a deer in the sweet spot and, once the arrow arrives, achieving the kind of terminal performance that guarantees a quick and humane death.

Back in The Old Days

You millennials don’t really understand how good you have it when it comes to choosing and using modern bowhunting equipment. Back in the 1980s, when compound bow and arrow shaft technology was starting to rapidly evolve, I shot a fingers bow set at 80 pounds and used a heavy aluminum arrow that, together with a 125-grain replaceable-blade broadhead, weighed in right at 545 grains and left the bow at roughly 220 fps. When I wanted to lighten things up, I went to a “Superlight” 2413 aluminum shaft weighing in at 446 grains that left the same bow at 250 fps — which was blazing fast at the time.

Contrast that with today. Modern compound bows can easily produce raw arrow speeds of somewhere between 260-280 fps, with some blasting over the 300 fps mark, using hunting-weight modern carbon arrow shafts. In 2018, I shot a 28-inch draw length Mathews Triax set at 70 pounds, 28½-inch Victory Archery VAPs, and a 100-grain Rage Hypodermic broadhead that weighed a total of 395 grains that left the bow at 291 fps. When I shoot the same arrows through a 65-pound draw weight Mathews Halon I still get arrow speeds of 274 fps.

To paraphrase Dinah Washington’s 1959 Grammy winning song, “What a Difference a Day Makes,” what a difference three decades make. Hunting compound bows, arrows and broadheads have evolved mightily down through the years. Today we are shooting fast arrows with lots of kinetic energy designed to make hitting the target easier than ever before, as well as provide the downrange “pop” needed to cleanly kill deer and other big game animals. Here’s why, when using today’s modern compound bows, I prefer the moderately heavy arrows.

Why K.E. is Important

Kinetic energy (K.E.) is the most important part of the arrow penetration story, though certainly not all. To determine how much initial K.E. your own bow-and-arrow setup has, you need know just two things: how much your arrow shaft weighs, including fletching and broadhead, in grains; and how fast the arrow leaves the bow at the shot. You then simply plug the numbers into the standard kinetic energy formula, which is mass x velocity x velocity, divided by 454,240.

In the above example, my arrow left the Triax with about 73.64 ft./lbs. of K.E., and the Halon with about 65.28 ft./lbs. of K.E. This is a lot of kinetic energy, way more than most experts believe is the minimum for hunting deer-sized game. That minimum number has been debated around archery circles for decades, but most of the people I respect have settled on a number somewhere around 40 ft./lbs. of K.E. at the shot.

However, you must remember that, because arrows decelerate rather quickly as they travel downrange, the amount of K.E. delivered on the target will be much less than initially generated. That’s why an arrow that will blow right through a deer at 20 yards might penetrate only about half the shaft length at, say, 40 yards.

Those light (8 grains per inch of arrow shaft length or less) arrows favored by many 3D shooters, speed-freak bowhunters, and archers who shoot light draw weight bows soak up less of a bow’s stored energy at the shot than heavier shafts do (any leftover energy not transferred from the bowstring to the shaft at the shot is instead transferred to the bow itself, which results in vibration). And, because they both soak up less energy at the shot and actually decelerate faster than heavier shafts the farther downrange they travel, they shed energy more rapidly than do heavier shafts. That means that after a certain point they deliver much less K.E. to the target. And trust me on this, even a difference of just 5% in K.E. can mean a big difference in penetration on game, especially bigger-bodied Northern whitetails.

But K.E. is Not Everything

In the penetration game, K.E. is not everything. If it were, bowhunters would be shooting arrow shafts that were light as a feather, since the lighter the arrow, the faster it will initially blast out of the bow, and therefore it would generate more kinetic energy since velocity is squared in the K.E. equation.

The other scientific principle involved is called momentum. Momentum is defined as “a property of a moving body that determines the length of time required to bring it to rest when under the action of a constant force.” In simple terms, momentum is considered to be a quantity of motion. This quantity is measurable, because if an object is moving and has mass, then it has momentum. In equation form, p=mv, where p is momentum, m is mass and v is velocity. Bowhunters don’t consider momentum as much as K.E. for several reasons, the most likely being the fact that as the speed of an object changes — and after the shot, an arrow begins to decelerate, meaning that for every foot of flight it is traveling at a different speed than the foot before — it is too complicated to play with in a simple discussion.

What you do need to know is that, all things being equal, heavier, denser objects traveling at the same speed as lighter objects will have greater momentum. That means it is more difficult to stop them, which means they will penetrate more deeply. An easy analogy here is visualizing both a golf ball and an egg smashing into your own ribs at the same speed. Which will hurt more?

Taking it a step further, when an arrow meets solid resistance at the target (think ribs or shoulder blades), its direction will be impacted. Again, the laws of physics are in play. A heavier body in motion has a tougher time changing direction than a lighter body, which means the heavier shaft will have less of a tendency to veer off target than the lighter shaft.

Shaft Diameter

One of the amazing things about modern arrow shaft technology is how manufacturers can build shafts of the same spine and diameter of different weights. What that does is give us options when selecting a shaft that has the correct spine to tune properly with our bow that can weigh pretty close to what we want it to weigh.

This helps us choose arrows that have much smaller diameters than those common in the days of yore. This is a good thing because another penetration factor is drag. In this case, that refers to the amount of resistance the shaft meets as it penetrates an animal. Small-diameter arrows — and today, there are hunting shafts with diameters as small as 4mm (which is .157-inch) — have less drag than larger-diameter shafts, and thus will penetrate deeper than fatter shafts, all other things being equal.

What About the Broadhead?

Broadheads and how they penetrate is another topic altogether. Suffice it to say here that one of the key factors in overall penetration is blade sharpness. Scalpel-sharp blades slice more cleanly and penetrate more easily than dull blades. One should never go hunting with broadheads that do not have blades so sharp they scare you.

Moderation in All Things

It all boils down to this: White-tailed deer are not overly large animals. They don’t have bodies that approach the size and muscle mass of an elk, moose, or even a large black bear. There’s no reason for compound bow shooters to use mega-heavy shafts more suited to hunting these larger animals — though there’s really no such thing as too much penetration. However, you can use shafts that are, in my opinion, too light. Super lightweight shafts won’t have as much K.E. or momentum downrange. They don’t soak up as much of a bow’s stored energy as heavy arrows do, meaning with each shot there is more stress being placed on your bow. And for those who hunt in open terrain where the winds tend to blow, a lighter shaft will drift off course in the wind more than a heavier arrow.

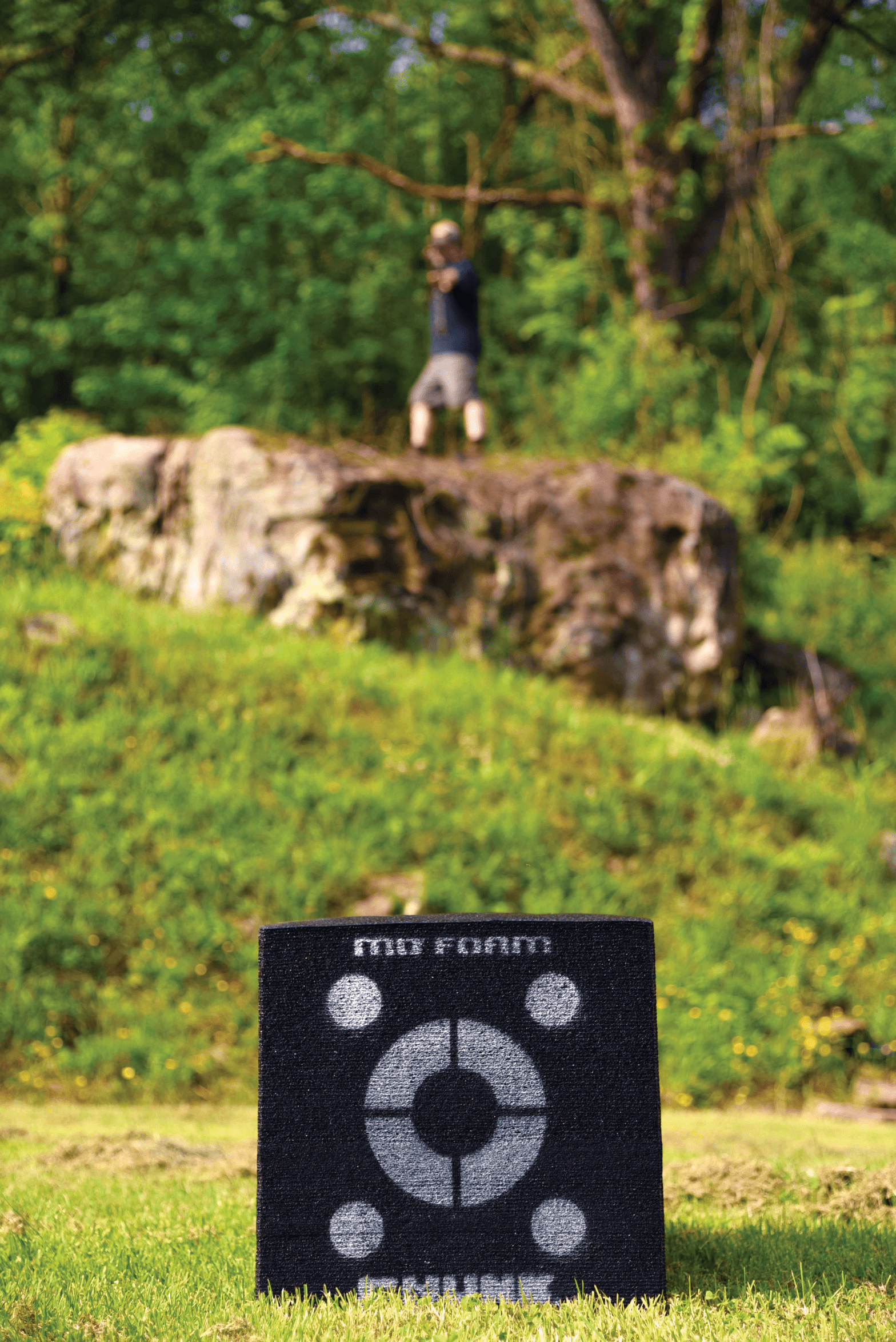

This is why the medium-weight hunting shaft makes the most sense. When choosing a hunting arrow, you want to blend the best of all worlds. You want to shoot the fastest arrow you can shoot to help flatten trajectory, yet you need to have enough K.E. and momentum when the shaft strikes the target to ensure deep penetration — preferably a complete pass-through.

You need that reasonably fast arrow speed even when using a laser rangefinder because game moves around a lot, walking in and out of shot windows in the brush. You may have taken a 30-yard rangefinder reading off a tree trunk, but when the critter walks a few steps in front or behind the tree and you don’t have time to hit him so you know exactly how far he is, the raw arrow speed offered by the medium-weight shaft makes a killing hit easier to achieve than with a super-heavy arrow. At the same time it will deliver the penetration necessary for a humane kill.

So … how heavy an arrow do you need to shoot? For the average bowhunter with a draw length somewhere between 27 to 29 inches and a compound bow draw weight of between 60 to 70 pounds, using an arrow shaft that weighs somewhere between 8½ to 10 grains per inch, minimum, will get it done.

With my own 28-inch draw length, I cut my shafts to 28½ inches and try and get a total arrow weight, including broadhead, fletching and nock of somewhere between 390 to 410 grains. If I can send that puppy off at somewhere between 270 and 290 fps from a 70-pound compound, I am very confident I can hammer any whitetail on the continent, even at longer ranges. For me, this is the ideal combination of weight, speed and stability necessary to achieve precise broadhead placement and penetration, every time. Isn’t that what’s it’s all about?